The Greatest Giants of Sherwood |

by Roger A.Redfern |

Country Life Jan 17, 1974 |

Old Sherwood extended from Nottingham

in the South to within a couple of

miles of Worksop in the North, to the

outskirts of Chesterfield in the West and to

Southwell and Laxton in the East. It was

always a scattered forest punctuated by broad

tracts of heath. The infertile Bunter sandstone

underlying the area has been largely responsible

for the salvation of the woodlands, for it

prevented it being cleared for agricultural use.

If Sherwood was spared by the farmer it

became an attractive prize for the carpenter.

In 1337 Edward III ordered the Prior of Blyth

to deliver 40 oaks to the King's carpenter for

the construction of a galley at Kingston-upon-Hull.

Major Hayman Rooke (who catalogued

the Sherwood oaks in the 18th century) records

that in 1609 a survey of the trees remaining

showed there were 49,909 in the portions called

Bilaugh and Birklands. There were 2,593 fewer

in 1689, a reduction that includes loss by

natural decay. But there was little thought of

replacement. Kilton Plantation, near Worksop,

was sown with acorns in 1763, but the ancient

heart of the Forest was not conserved in this

way.

By 1790 a survey showed that there were

only 10,117 trees remaining in Bilaugh and

Birklands, valued at £17,147 15s 4d. Two-thirds

of the trees had gone in a century,

many for timber and many cleared for convenience

when the great estates were being

enclosed from the Forest. In 1707, for instance,

the Duke of Newcastle obtained permission to

make a 3,000-acre park at Clumber, and in

1709 he was allowed to make "a broad riding-way

through Birklands Wood, of a width of

80 yards". The value of the timber cleared to

make this ride was £1,500.

Though the formation of the great estates

resulted in the natural Forest area being

reduced, what was left within their boundaries

was to some extent safeguarded from later

depredations. Most of the greatest trees

remaining today are found within these estates.

One exception is the best known of all-

probably the best-known tree in Britain-

which stands in the Birklands area of

Sherwood, a mile North of Edwinstowe. It was

formerly called the Queen Oak, but more

recently has come to be known as the Major

Oak, whether due to its great size or to

the memory of Major Hayman Rooke is a

matter for conjecture. It stands at the northern

extremity of the newly established Sherwood

Country Park, in the care of Nottinghamshire

County Council. This great tree has a girth

of 64 feet, and it is claimed that 34 children

can get inside its hollow trunk.

The Major Oak is undoubtedly the most

popular spot in the Forest area, and the path

to it and ground around it are now devoid of all

vegetation because of the number of people

that have stood upon the infertile sandy soil.

What a contrast with pictures of the tree two

centuries ago when an old man kept fowls

under the venerable giant. It was known at

that time as the Cockpen-tree. On August

Bank Holiday Monday, 1957, no fewer than

15,000 people came to look at the Major Oak.

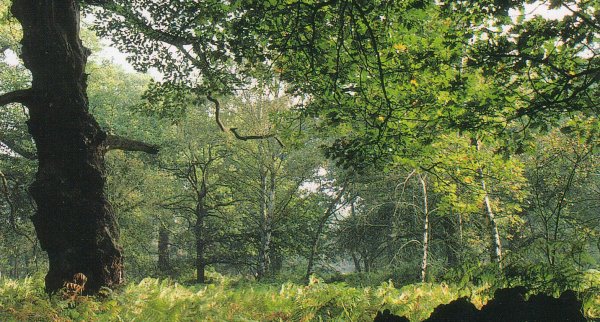

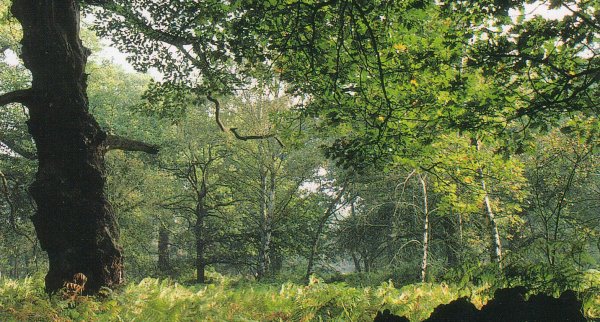

In that part of Birklands to the West of

the Major Oak is an area dominated by the

remains of decaying oaks - "stag-headed oaks".

Most of the trees of Sherwood are either sessile

or pedunculate oaks, both deep-rooting

species. During this century local water

undertakings have extracted vast quantities

of water from the Bunter sandstone layers

under the Forest. The water table has been

lowered (aided by new coal-mining developments),

resulting in the slow death of many of

the great oaks, hence the "stag-headed" form

because the trees tend to die down from

their outermost branches. It is amazing to find

so many huge oaks so near death and yet still

managing each spring to send out new foliage.

At the heart of Birklands stood the most

famous blighted oak, called the Shambles Oak

or Robin Hood's Larder. Inside its hollow

trunk were iron hooks upon which was hung

stolen venison. Writing in 1913, Robert

Murray Gilchrist reported that the tree had

been set on fire by a picnic party some years

before and that there is "something pathetic

in the valiant greenness of its scanty leaves.

It is like an old, old man who will be brave to

the end." That end came about

eight years ago when the ancient

shell was finally blown down by

the wind. Between the Major

Oak and the site of Robin Hood's

Larder and extending from North

to South is the 80-yard wide

"Duke's Ride" already mentioned.

Halfway along this

straight ride is the fine Centre

Tree. Unlike so many of

the notable oaks of the district

this specimen, probably planted

soon after the ride was formed in

1709, is in its prime.

Of the great estates enclosed

from the Forest undoubtedly the

richest in old oaks was Welbeck

Park. Some of the giants have

now decayed and gone for ever,

others still adorn this, the seat of

the Duke of Portland. It was

recorded in 1875 that "Welbeck

contains 2,283 acres, 3 roods,

3 perches of land and anciently

formed part of the Manor of

Cuckney, which was held by

Sweyn, a Saxon". Major Hayman

Rooke described the finest trees in

his Descriptions and Sketches of

Remarkable Oaks in Welbeck Park,

published in 1790. The Duke's

Walking Stick was an oak

"perhaps unmatched by any

other in the Kingdom for height

and straightness". It has long

since disappeared but in its prime measured

111 feet 6 inches in height, contained 440cubic

feet of solid timber and weighted 11 tons.

Upon the gentle slope of Hagg Hill, to the

East of Repton's Great Lake, grew the Seven

Sisters Oak. This had seven trunks growing

from one root to a height of 90 feet. In 1873

it was reported that "the circumference at the

bottom is about 30 feet. Several of these stems

were long since blown down". A pair of

ancient oaks still stand on either side of the

main drive from the Lion Gate to Welbeck

Abbey. At one time a huge gate was hung

across the drive between them, and for this

reason they are known as the Porter Oaks. In

1875 Robert White recorded that "the height

of one is about 100 feet, and its circumference

about 38 feet; the other is about 90 feet high,

and about 34 feet in circumference". The trees

are now much reduced in size, having been

capped with lead to protect them from the

elements. But they are still impressive, backed

by younger conifers and the sweep of the park.

Of all the trees of Sherwood the most

remarkable is the Greendale Oak. It

stands almost unnoticed at the centre of

Welbeck Park, half a mile to the South of

Welbeck Abbey. Once probably the greatest

tree of the Forest, the first Duke of Portland

said that he could drive a carriage through it

and in 1724 had an arch cut out of the trunk

to prove his claim. The timber removed was made into

a cabinet for the countess of

Oxford three years later. It contains

inlaid pictures of the tree

and the Duke of Portland driving

a carriage and six horses through

the arch. The cabinet is still at

Welbeck.

Major Hayman Rooke considered

the Greendale Oak "to be

above seven hundred years old"

in 1790, while in 1797 Throsby

said "it is supposed to be upwards

of 1,500 years old". In any event

the tree never fully recovered

from the removal of the archway

and during the last century it was

"planked diagonally and otherwise

supported". Chains were

later fitted to hold up its spreading

branches, at that time still extending

over a diameter of 45 feet

Today this former glorious

giant is but a tumbled heap of seasoned

timber, festooned still with

old chains and wooden supports.

Standing beside it, though, one

can appreciate its monstrous

proportions at its prime:

Whose head above his fellow of the grove

Doth tower, as these above the sward beneath.

|