I estimate the distance from home to school at about a mile and a half. Quite a distance for a four-year old to walk, and unaccompanied at that. Such a thing would be unthinkable today, what with traffic and predatory grown-ups. Evidently, neither was present then. I don't know whether I returned home for lunch, or stayed in school. It doesn't seem possible for me to have returned home. I do remember coming home sometimes. I have a sharp image of my mother standing in Bryn Road, and, of myself, walking diagonally back and forth, across it, and of suddenly becoming aware of her presence, standing waiting for me further down the road. Ashton was not very big. It couldn't be when a small child could walk to school from one side of it to the other. A coal and cotton town, it was of many in the area between Manchester and Liverpool, which was the birthplace of the industrial revolution. I have mentioned the Record mill. There were others in nearby communities. As for the coal mines, besides the Crow pit, there were Smetherts and Garswood Hall, and others. The coal mines accounted for the polyglot population. In addition to the native Lancashire stock - probably my ancestors on my mother's side were of this sort, her maiden name was a most unusual one - Blinstone - there were considerable admixtures of Welsh and Irish. The Welsh probably came because they already had experience of working in mines at home. The Irish had no such experience. There were no coal mines in Ireland. Their experience was working on the land, and, at first, they came as seasonal workers. They were big and strong, and hard workers. They also earned a reputation as heavy drinkers.

p.20 Gradually, the Irish became a part of the community. Instead of working for a season in the mines, and then returning home to help with the harvest, they stayed permanently. By degrees, they married local girls and settled. The flourishing Catholic schools and the Church, the most imposing building in Ashton, were indications of the degree to which this had occurred by World War I. My father and his family were typical of this movement. His father, Peter, came seeking work and found it in the coal mines. He brought John and James with him. My father stayed in the small town of Kiltimagh in County Mayo until he was about seventeen. There he worked for an Aunt who had a small holding of about six acres. Life was hard and pretty primitive, digging lazy-beds for potatoes, cutting the peat and bringing it in from the bog to be carefully stored and dried, feeding the pigs and chickens, and tending the cow. The small cottage had an earth floor. The only source of heat was the peat fire that was always kept burning. The little time left for diversion was taken up by walking into Kiltimagh itself, or to the slightly larger town of Castlebar, about eight miles away. Not that either community offered much in the way of entertainment beyond sing-songs in the bars. So, when my father left his aunt's place, and came to Ashton, it was almost inevitable that, he, too should go into the mine, and, having settled down, to be married to a local girl. Acceptance of the Irish was grudging. There was the religious difference. The locals, for the most part, were Protestant. There was also the reputation, well earned, for hard-drinking and fighting. And, in addition, there was the widespread idea, true or not, that the Irish were dirty, slovenly, and generally disorderly in their way of life; that Irish families had large numbers of snotty-nosed waifs; that they had chickens walking on the kitchen table; and that Paddy took his pig to bed with him at night; and that you weren't safe wandering into a predominantly Irish area - what, today, we would call a ghetto. Such were the stories circulated.

p.21

Planned attacks upon them were not uncommon in earlier times. I used to listen to the story of such an attack. Some men stationed themselves at night at a convenient spot that people had to pass on their way home. As each man passed, a voice would call out: Like the Irishman, some of the Welsh miners came on their own. They would find lodgings with a family. There were many families who were only too glad to have a paying guest in the house, even if he was Irish or Welsh, for it meant a little badly-needed extra money. Some of these single men stayed with the same family for years, eventually becoming, to all intents and purposes, a member of the family, whose habits and likes and dislikes were thoroughly understood and catered to. One of my grandmother's neighbours had a lodger who was called to get ready for work partly in his native tongue. "Pimp o glock, Mr. Davies", his landlady would call. Five o'clock, time for him to rise, and start the preparations for going on to work at 10:00 p.m., the night shift. I was even taught some numbers in Welsh - in, di, tri, pedwad, pimp. What do I remember most of the life in this small town? One memory is family gatherings. There would be a ham tea, a table laid out with a fine table cloth and the best china and cutlery. Aunts and cousins busy cutting mountains of bread and buttering it, setting out the cakes, preparing the tea. As children we mostly got in the way, but nobody minded so long as we did not interfere with the contents of the table. If you were suspected of delinquency, you were warned off. Sometimes, the warning came too late. Harold Caunce was a bit of a devil. One day, at the height of preparations for a tea, Harold Harold is round the table sticking his finger into this and that. "Harold, stop that! Harold, get away! Harold, don't touch!" The warnings were of no avail. In a cunning move, when all attention was elsewhere, Harold saw his opportunity and stuck his finger into a pot containing some brown substance. Auntie Winnie, I think it was, spotted him as he was popping his finger in his mouth.

p.22

After tea, the conversation at the table was adjourned to the fireside. Bits of gossip and local news were followed by stories about the old days, when they were young, very often involving eccentric characters and their own adventures. Such eccentrics included Mucky Tuppy and Owd Pinner. Mucky Tupper would swallow a mouse any time if somebody would buy him a pint to down it with. Owd Pinner evidently had a wife who constantly replied to any information he gave her with: "I know." He resolved to teach her a lesson. In those days, there was a chamber-pot under each side of the bed. The need frequently arose during the night, and there were no indoor toilets. So one day he smeared the rim of her chamber-pot with glue, and replaced it under the bed. Then he waited. Sure enough, he was wakened during the night by his wife's cries. "What's up?", he asked. There were stories of their schooling. Evidently, the older ones had to take "school pennies" to school with them to help defray the costs of their education, for they had gone to the National School, which had been run by the Church of England. They told stories of going to work, and of helping at home, washing, sewing, darning, etc. Some of them had had to go down to the slaughterhouse when pigs were being killed, to bring back the blood which grandmother used to make black puddings, the sale of which helped to keep the family afloat after she had been widowed. They also repeated yarns about the strange antics of the inhabitants of nearby villages. In one place, the people were reputed to put the pig on the wall to watch the band go past: in another, they were known to Ashtonians as Cay-yeds (Cowheads) because it was told that in that place once a cow got its head through some iron railings. Many of the villagers came to look and to give their advice as to how the problem should be resolved. Eventually, the solution decided upon was to chop off the animal's head. One story would lead to another. It was a warm, exciting atmosphere - the fire blazing, the stories bouncing around the circle, and lots of laughter. Of course, we children were not allowed to speak. Only to listen. And sometimes we were the subject of the conversation as if we had not been present. We were all thoroughly discussed - Our Dora, Our Chris, Our Gerald, Our Frank, Our Eddy, etc. We were compared, too, I think, and there was a certain amount of quiet bragging, and possibly, some jealousy. Auntie Polly, especially, focused on Our Eddy. Auntie Winnie, strangely enough, rarely referred to Dora as Our Dora, which was the acceptable northern working-class way. Dora was almost invariably Dora.

p.23 I have no doubt that to her that it was nothing, and soon passed from her mind, but it stayed with me almost as a shame for many a long year. Other memories of Ashton remain. The market is vivid with its long rows of stalls selling its cloth, cheese, vegetables, chinaware, meat. In the family, they talked of Dick Kay who had a butcher's stall on the market and a shop on Gerrard St. backing up to the market. He had done well, become quite well-to-do selling lamb, they said, for five a leg and four a shoulder (fivepence a pound for leg and twopence for shoulder). I remember, incidentally, another butcher. His name was Mr. Hotchkiss, and I remember him and the lady who worked in his shop, probably his wife. I was always made a fuss of there. At the corner of the market, down at the Steam Engine end, was a bakery, full of fragrant breads and delicious-looking cakes, and always a whole boiled ham, the outside adorned with golden bread crumbs. Very thin slices of pink, succulent meat were cut to the customer's order. Across from the market, on the opposite side of Gerrard St. was the Rec. For the most part, it was an expanse of rough grass-covered land on which children could run wild. But it also contained a club house and a bowling green, which provided recreation in the summer months for both men and women. Another thing that springs to mind is the custom of "walking days". This was widespread throughout Lancashire. At Whitsuntide, the children, all dressed in white, would walk in procession through the streets of the town. For weeks before, mothers would be busy making the girls' dresses, and on the day, Whit Sunday or Palm Sunday, the town would turn out to watch the parade. For all these activities within the town, people walked or biked. Cars were unknown, or very scarce, at that time, and only a few people had a horse and trap. In any case, the town was small enough to make walking to any part relatively easy. If one wished to go further afield, one walked, if the distance was reasonable. We always walked to and fro between Ashton and Haydock where the Caunces lived. For longer journeys, there was the tram, which was reliable and cheap, though not very fast by our standards today. By this means, one travelled to St. Helens, Wigan, or Warrington, all of which were bigger towns with more interesting shops, and were within a few miles of Ashton. It was on a tram, incidentally, that I managed to embarrass my parents. I had evidently, just turned five, the age at which children had to be paid for.

p.24 I never lived that down. The tale was told and retold around the family circle for years. It must have been on one of these outings that I got lost in Warrington. All I remember is being in a large shop in the company of a lady and a gentleman who were unknown to me. As is common with young children I had wandered off on my own. I don't recall being frightened or upset, and was soon reclaimed none the worse for wear. For longer journeys, there was the train. If you wanted to go to Manchester, or Liverpool or Southport for the day, that was the way to go. Trains were frequent and there were cheap day return fares available. I had only a hazy idea of local geography. I used to listen to my aunts talking about many places. Carmel, where they went for picnics; Knowsley Hall, the home and estate of the Stanleys, Earls of Derby; Haydock Park where the racecourse was; Billinge, Bryn, Atherton, Earlestown, Newton-in-Makerfield, all nearby communities. And Stubshaw Cross, which I remember, because it was there that I first encountered migraines. Stubshaw Cross was in the opposite direction from Potter's Row to Ashton. I had walked down the lane by Pimblett's farm, past the first field, and then turned right, and followed the path till it joined the road at Stubshaw Cross. All I remember there was a pub on the corner and people passing, and myself sitting on the kerbstone by the road, being extremely sick and feeling deathly ill, a long way from home, and wondering if the world had deserted me. A desolate feeling, and one that I shall never forget. Strangely enough, I have no idea how I got home, but I never forgot Stubshaw Cross. Such are the recollections of the place where I spent my six or seven years of life. A small, drab, undistinguished place in the eyes of the world, then as it still is. I have met very few people who come from Lancashire who admit to knowing it. Even people from Warrington some six or seven miles away. To explain to them where it is, one has to mention Haydock Park. Oh, yes, of course, they know where Haydock Park is. Everybody knows that because of its racecourse. Then you explain that Ashton is a mile or so away. But from birth to six years, it was my world. The Crow pit tip, Pimblett's farm, Potter's Row, the houses of dark red brick, the mill, the market, the cobbled streets, the trams, schools and church, men in dark suits and women in shawls. And providing a base for exploring this world, the circle of family, the centre consisting of the nucleus of aunts, and on the periphery the uncles.

p.25

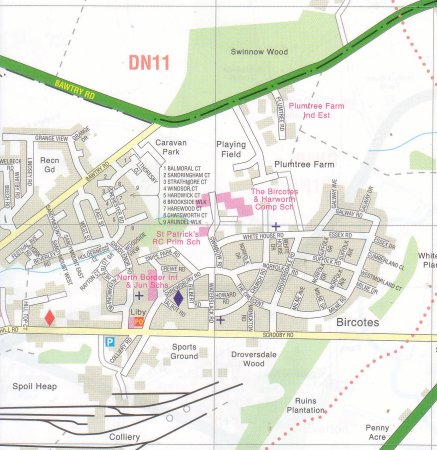

BIRCOTES

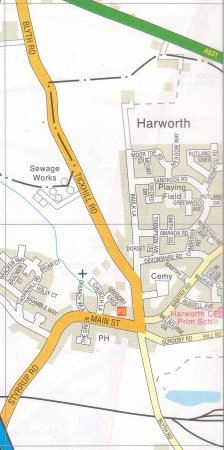

The village of Bircotes lay across the road from the colliery at the end of the line of shops, dominated by it, as, indeed, it was in every way. It was the reason for the village's existence, the sole employer of its workers. It must have been in 1924 that we arrived there. Building was still in progress. My memories of our stay there - just over a year - are vague and indistinct. Although I was six years old, I do not remember arriving. I do remember our address - 23 The Crescent - and the fact that there was building going on nearby, for the village was not yet complete.

p.26 It must have been during this time that Joan was born. She is six years and six months younger than I; Frank, is four years and four months younger, so he must have been about two. I mentioned Joan's birthday because I do remember our two doctors - both Irish - Dr. Quigley and Dr. Lafferty - and they would be visiting our house, as was the common practice for physicians in those days. The only other persons I remember were the Phasey families. I suppose Ernest Phasey was a workmate of my father's. He was a veteran of the Great War, one of the Old Contemptibles, the British Expeditionary Force, and so-called because the German High Command referred to them as a "contemptible little army". Mr. Phasey's pride in being a member of this gallant band which slowed down the German advance into Belgium and northern France at the beginning of the war was reflected in the name of the couple's only daughter, Courtrai, after a town there. We used to go to the Phasey's for Sunday tea, or they would come to our house. Afterwards, in the summer time, it was a common practice for families to walk together, the men in their blue serge suits walking ahead, while the wives walked together at a distance behind, taking charge of the children. In this way, we would walk to nearby villages - Bawtry, on the Great North Road which connected London and the northern cities, with its old inns and staging houses where the coach-horses had been changed, or Scrooby, with its tiny church, famous as the home of John Brewster, one of the leaders of the Pilgrim Fathers who came over to North America in the Mayflower in 1620. My general impression of Bircotes is of a certain dullness about the place. Architecturally, it was designed to be interesting. Older mining villages - and including small towns like Ashton consisted of rows of houses, often back to back, each with a small back yard containing an outhouse, and no front garden - ugly, monotonous and dreary. The newer villages, such as Bircotes, were designed to be more interesting and liveable. The streets were in interesting patterns; the houses, set back from the streets, had both back and front gardens. Also the houses were equipped with an indoor toilet and a bath. All this was intended to humanize the environment of the miners and their families, and it was a great improvement. Nevertheless, there was something lacking. The place was new. It had not had time to develop into a community. The population was a mixture of people newly come from older coalfields - Yorkshire, Wales, Staffordshire, Lancashire, Durham and Northumberland - all of whom, in a sense, were refugees, seeking a better life.

p.27 So, the sense of connection, of belonging, that one felt in a place such as Ashton, was lacking - the bonds of family, the familiarity of well-known places and things, the routines determined by usage and tradition. This is probably why my mother took to going back to Ashton for brief trips. How many, I don't know, nor for how long. But I remember her not being there, and my father being in charge. He was not very good in the kitchen. We would get badly burned bacon and blackened eggs. He tried. I remember him trying to figure out how to make rice pudding. Did you put salt in it? Yes. How about pepper? Don't know about pepper. What does your mother do? We put the pepper in, anyway, and it didn't help the pudding. I often wonder why I remember so much more about Ashton than about Bircotes. Of course, we were there only for a year or so. That might be a part of it. Perhaps, as I have suggested, the dullness of the place might have had something to do with it. Maybe, it was a phase that, at six years of age, I was going through. In the spring of 1926, we moved from there. Not very far. Langold is only half a dozen miles as the crow flies. Another modern mining village, with a new colliery, and a new village, with people from all over the country. Just like Bircotes, one might say, but, unlike Bircotes, destined to play an important part in my young life.

p.28 The year was 1926; the reason for the violence was the General Strike, in which the workers in the country's principal industries, resisting the demands of the employers for wage reductions, downed tools and walked out of factories, and mines, and off trains and buses. The employers, in their turn, attempted to beat the strike by using substitute labour - what the workers called "scabs". For a time, the country seemed about to dissolve into chaos and violence. Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary, called out the troops to maintain order, and to man the docks. In some towns, students and bank clerks manned the buses. In the mining industry, the owners used the labour of those willing to brave the picket lines, and to endure the opprobrium of being labelled as "scabs" who would break the miners' solidarity. They also employed puppets to set up alternative units to the N.U.M. (National Union of Mineworkers) with whom they could negotiate, and through whom they hoped to undermine the N.U.M. The temptation to go to work was great, even though one became a social leper thereby. One might even avoid the worst consequences of "scabbing". The owners would draw workers from one mining village and transport them in buses to work in a mine a few miles away; only a few "scabs" came from their own village, and for them and their families, ostracism hit hard. Those who were tempted, however, received a wage every week, which enabled them to feed and clothe their families. The strikers, by contrast, depended on a small weekly allowance from the dwindling union strike fund, barely enough to put food on the table. As for replacing worn-out shoes or clothes, there was no hope of that. Make and mend was the way. Mothers stitched and sewed; fathers often repaired shoes. That is, if they were good parents. Some were, others were lazy, or feckless. Their children were the ones with their britches backside out, or footwear with great holes in the soles. For these, the soup kitchen was a boon. This was a contraption consisting of a boiler on wheels, in which a thick beef and vegetable soup was brewed whenever supplies were available. Women and children - never men - would walk to where it was situated, carrying jugs or bowls, and received a portion according to the number in the family.

p.29 Such was the state of affairs when we arrived in Langold in the spring (I think) of 1926. I was to live there continuously until I left to go to University in Sheffield in the autumn of 1936. It was a new village, very much as Bircotes was, one of the new "model" villages. It was planned as a unit: with broad streets, curving avenues, and houses built in twos and fours, instead of the long, faceless terraces of older worker housing. Each house had electric light, a bathroom with a bath, a w.c. just outside the backdoor but still within the main building, and a coalhouse separate from the house but joined to it by a bridge or arch of brickwork. At the front and back was a large garden space. When we arrived, it was still half finished. Only the houses near the main road were finished. The more one moved away from that road and into the village proper, the less completed were the houses until at the top of the village, construction was in its rudimentary stages. Here was a place of adventure. Houses with floors half completed, walls newly plastered, or covered with a framework of laths ready to take and hold the plaster, tangles of pipes and electric wires, stairs leading up to bedrooms and bathrooms complete with a tub. And outside, the usual chaos of a large building site; stacks of wood for beams and flooring, piles of bricks, stacks of roofing tiles, glossy brown sewer pipes, great pits of slaked lime for making plaster into whose jelly-like depths we threw whatever came to hand. It was a great place for running wild, playing out whatever fantasies came to mind, and free of menace, save for the danger of falling into the lime pits, for I can recall seeing no watchmen on duty when the bricklayers, hod carriers, plasterers, carpenters, and navvies had gone home for the day. Our visits did frequently have a useful purpose; all around lay pieces of wood - broken laths, trimmings from beams and flooring - which we collected and took home for kindling. There they were chopped into "sticks".

p.30 The whole village was designed to consist of about four hundred houses, a "model village", as I have previously said, in which respect it was similar to Bircotes. But unlike Bircotes, which was on a road which seemed to come from and go to nowhere in particular, Langold was on the main road from Worksop to the south, to Doncaster on the north situated on the Great North Road. Both were sizeable towns; both had long histories. Worksop Priory was a church going back to the 14th century, while Doncaster had been a Roman settlement called Danum. From Worksop the road runs north, passing through a string of communities - Carlton-In-Lindrick, Langold, Oldcoates, Tickhill and so to Doncaster, a distance altogether of about sixteen miles. As in Bircotes, the village shops lay on the east side of this road, and the village itself on the other. Not good traffic planning, one might say, but, in those days, there was very little traffic. A local bus company ran a service to Worksop, a distance of about five miles. Underwood's later called the East Midland, travelled between Doncaster and Worksop, and from there to Nottingham. Cars and lorries were few and far between; so much so, that one of our pastimes was to sit at the side of the road with a pencil and a piece of paper, and write down the registration numbers of all vehicles that happen to pass.

p.31 The entrance at the south end was marked by the Wesleyan Methodist chapel, a red brick structure, which I never once entered during the whole of my time in Langold. I used to see people near it and going in and out - children going to Sunday school and older people going to and coming out of service. The chapel marked the beginning of Church Street, which ran along the south, and below, was "the cut" containing the sidings where the rail cars for the coal were marshalled. Beyond that lay the colliery, Firbeck Main, that was the reason for the existence of the village. When we arrived there, the work on the cut was still going on, and I remember watching the big steam shovels - they were called "American Devils" - at work, huffing and puffing, and jangling, as the great jaws dug into the earth. Church Street was well-named, for in addition to the Methodist Chapel on the corner of the main road, there was, further along, a Church of England, and a Salvation Army. Beyond these, there were houses on both sides of the road, until the road came to its end, and debouched into a path in the woods which extended along the whole western side of the village. If one took a fork that bore to the left, it was a short walk, downhill at first, then up a short sharp rise to the lake. So, Church Street was well travelled. People coming along Williams Street and White Avenue, going to the lake, fed into Church Street. I mention Langold Lake because it was an important part in the life of the village. People of all ages went there for diversion. Immediately before the rise that took one up to the lake, a large playground was built, where children could disport themselves on a variety of swings, roundabouts and other vertigo-inducing devices. Around the lake itself for much of the way, there were, at intervals, rickety stages which took the fishermen beyond the fringe of reeds. There they would sit by the hour, with their lines in the water, a small tobacco tin of sawdust and maggots nearby, watching the quill-like float for signs of a bite. Their reward seemed small - occasionally a small roach or perch - and very occasionally, someone would pull in a pike, a much bigger fish, with a long mouth lined with vicious-looking teeth. There were a couple of rowing boats, too, that fishermen could use if they chose, but they eventually disappeared. The far side of the lake was more interesting, as far as I was concerned. Here was a swimming pool, a rectangular concrete structure. It had a row of changing cabins alongside it. The shallow end was very shallow indeed, where water entered from the lake to fill it, and replace the water draining out slowly at the deep end. The deep end itself was about four feet deep. In the summer, this pool was packed with children. Their cries could be heard a mile away, and hastened the step of other children hurrying after school with their swimming costumes and towel rolled into a neat bundle and tucked under their arm.

p.32 I had just taken you beyond the gate into the field beyond. This was where there was a great deal of action. There was a large changing hut near the lake. Further up the slope was a bandstand, where on holidays and special occasions, the colliery band filled the air with music. I loved it then and still do today - the sound of a prize band in the open air is wonderful. At such times, there would be food and ice cream stands, and lots of people sitting on the grass or strolling around. We, as small boys, used to get terrific enjoyment from running madly around and wrestling each other on the grass. Behind the bandstand, the field continued towards the colliery buildings and the pit tip. We didn't go up there much. Sometimes, we used to walk up and watch the pit ponies. These diminutive horses worked down the mine pulling the tubs of coal from the coal face to the pit bottom, where they were loaded into the cages and brought to the surface. After some months of continuous work underground, the ponies began to go blind, so they were brought to the surface for rest and to restore their eyesight. At the lake itself, and jutting out from the shore, there was a pier of some twenty yards in length. It was about five feet wide, made of wood, and supported on barrels. Out into the lake some forty yards or so was a square, flat free-floating raft, also supported on barrels.

p.33 If you proceeded from that field, through another gate, you came into another meadow, with a path which followed the line of the lake. A quarter of a mile along this path, you came to the head of the lake, and to the stream which fed it. Here was a stone bridge, and an old boathouse built of stone, and for long years in disuse, and now in disrepair. It was easy to imagine the days when the landowner who had built it, and his friends and family, would use the elegant boats moored alongside the stone jetty. The bridge crossed the stream and led to the other side of the lake, along which the path continued through another meadow to complete the circuit. Along this side of the lake were most of the stages used by the fisherman, roughly built mainly from tree branches laid in a corduroy pattern. Most people confined their visits to the area of the pool and the first field. We used the rest. At all seasons; in the summer for quiet walks, away from the boisterous noisiness of the swimmers: in the spring to look for tadpoles, and, later, for the thousands of tiny frogs that came hopping out of the water and towards the land; in the fall, to savour the colours of the leaves and the smell of ripe grass and decaying leaves in the sharp October air; and, in the winter, if we were very lucky, the days of hard frost would transform the lake into a vast area of ice. We were drawn to that as to a magnet. As the ice formed, we watched the hard blue sky and prayed that it would stay, and keep freezing. Then we would test the ice by stepping out gingerly from the shore; only a step at first, and then, by degrees, further and further out. Sometimes, we threw stones on to it, and these would bounce away over the ice, sending clunking echoes across the length and breadth of the lake. Once assured that our luck was in, and the ice thick enough to bear our weight, we set about getting equipment, either digging out skates that had lain rusting in some corner, or trying to persuade parents to let us buy some from the ironmonger's, - if we could find them, for skates were not in great or steady demand. If you were lucky enough to get skates, you attached them by their clamps to a pair of boots, and you were ready for action. Freezing years were few and far between, which meant that each time there was skating one virtually had to learn again. So we were not graceful.

p.34

OUR FIRST HOUSE

p.35

Miss Limb's and the adjoining fish and chip shop was a gathering place for children. Both were open far into the evening, so both were lit up; and there was a lamp-post on the street as well. Many hours were spent, standing around, watching the traffic to the shops, looking over the merchandise, discussing the merits of the sweets on display, and, sometimes, seeing a friend or acquaintance make a purchase. On leaving the shop, this unfortunate had to run the gauntlet of whining, cajoling, or even, sometimes, threatening beggars. Most sharing seemed to be done by lads who worked together to steal things from the shop - a bit of yeast from the bag under the scale, an apple, or a handful of sweets quietly taken from a box in the window. We had some of these in my classes as I went through school. Eric Watts, big-boned, gingery-haired, and fair-skinned worked sometimes with Johnny Gaunt, small, compact, bullet-headed and mean. But mostly, boys were afraid of being caught, reported to parents, and promptly punished. If father got to know, it was most likely the belt that each miner wore. Not a pleasant prospect. Not to mention all the gossip among the womenfolk, who made it their duty to spread the news.

p.36 The entrance to the mine from the road was quite imposing. A large semicircular area enclosed by a brick wall led through the wide gates down an avenue to the surface buildings. On the right was a large brick structure housing the company offices. This was the domain of Mr. Godber. Beyond this, and still on the right stretched a line of the old farm buildings, low and stone-built. Regularly whitewashed. These now served new purposes. One was a meeting room, another a bar with a billiard table. Beyond these was a bowling green and beyond the bowling green a wooden tennis pavilion and four tennis courts. From the old farm buildings, you looked across the cricket field to the officials' houses on the other side. The main mine structures lay on the left; a pithead baths where the miners coming off shift in their "pit dirt" showered and changed into clean clothes. Only the most modern pits had baths, and these were achieved only after long battles between workers and management. Men working in the older mines went home in their working clothes, and in their "pit-dirt" covered from head to toe in black dust. Further on the lamp shed: and beyond that the headgear with the two enormous wheels turning incessantly. Beside the headgear, the pump house, and the huge chimney that vented the smoke from the boiler-room furnaces. The great shops, where the fitters carried out the necessary repairs to all the equipment. And finally, the concrete tower where the coal was washed as it came up the shaft, and put on the screens where it was sorted for size, and bits of stone and bat were picked out and thrown aside. Beyond it all was the tip where the stone and dross was discarded on an ever-growing mountain.

p.37 To be able to tolerate working down the pit one had to start while quite young. Most of my schoolmates in Langold left school at fourteen and went into the pit, there to spend their working life, until they retired as worn-out old men, or were retired prematurely due to such disabilities as silicosis or nystagmus. Silicosis is a condition caused by the presence of tiny particles of rock in the lung which eat away at the tissue until breathing becomes difficult, and the victim is incapable of even the slightest physical exertion. Nystagmus is caused by spending long periods of time in the dark and dusty workings. It causes the sufferer's eyes to flutter uncontrollably.

The youngest entrant to the pit was first given a simple job. Door-trapping was one. The boy sat at one of the doors or gates underground which controlled the movement of air through the working. It was his job to open and close the doors to allow the movement of "tubs", small wheeled vehicles, which moved the coal from the coal face to the pit bottom. Experience saw him move gradually into other jobs, until he finally became a coal-getter working at the face, or a ripper working in rock. The few who trained and became deputies were responsible for shot-firing, which required expertise so that the danger of an uncontrolled explosion or dangerous roof collapse was minimized.

|

All Rights Reserved.

All Rights Reserved.